10 Defining Characteristics of Gothic Architecture

The Gothic technique - extending from the 12th to 16th centuries - was a predominant architectural style of the medieval era, bookended by the Romanesque and the Renaissance periods. It marks a definitive shift from the earlier 'dumpy' Romanesque churches to lighter, taller cathedrals - the changing socio-religious climate wrought structural innovations that revolutionized ecclesiastical architecture.

The name 'Gothic' is retrospective; Renaissance builders scoffed at the whimsical construction devoid of symmetry and used the term as a derisive reference to the barbarous Germanic tribes that pillaged Europe in the third and fourth centuries - the Ostrogoths and the Visigoths. Gothic architecture was erroneously seen as the product of a largely uncouth, chaotic, and superstitious era, while the truth was very different. It has since come to be regarded as the ultimate icon of scholasticism - a movement which sought to reconcile spirituality and religion with rationality.

Gothic architecture is acknowledged for spawning new structural marvels, phantasmagorical plays of light, and raising the bar for cathedral construction everywhere - even by contemporary standards. Here are some characteristics your standard Gothic cathedral will showcase.

Spires

These are tapering architectural elements that often replaced the steeple to lend an impression of loftiness. Gothic cathedrals often feature profuse spiring, giving the impression of battlements - symbolic of a religious fortress protecting the faith. Openwork spires are perhaps the most common; this elaborate spire consisted of stone tracery held together by metal clamps. It had the ability to achieve radical heights while lending a feeling of lightness through its skeletal structure.

Flying Buttress

Spider-leg-like in appearance, a flying buttress was originally instated as an aesthetic device. Later, they were converted into ingenious structural devices that transferred the dead-load of the vaulted roof to the ground. To add a degree of stiffness to the structure, they were stepped back from the main wall and connected to the roof via arching supports. The buttress now ‘carried’ the vault, freeing the walls of their load-bearing function. This allowed the walls to become thinner or almost completely replaced by glass windows, unlike in the Romanesque where walls were massive affairs with very little glazing. The buttresses enabled Gothic architecture to become lighter, taller and afford a greater aesthetic experience than before.

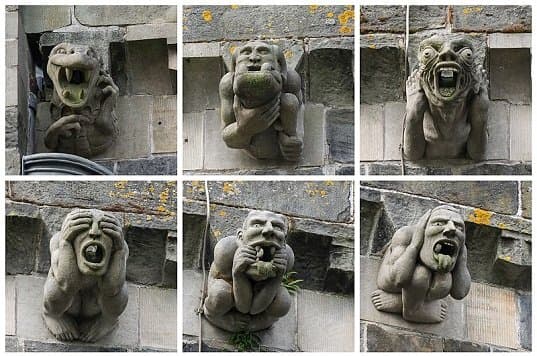

Gargoyles

The gargoyle (derived from the French word gargouille, meaning gargle) is a sculptural waterspout, placed to prevent rainwater from running down masonry walls. These numerous grimacing sculptures divided the flow among them, minimizing potential water damage. Gargoyles were sculpted on the ground and placed as the building neared completion. St. Romanus is often associated with the gargoyle; legend speaks of him saving Rouen from a snarling dragon that struck terror even in the heart of spirits. Known as La Gargouille, the beast was vanquished and its head mounted on a newly built church, as an example and warning. While the gargoyle has been around since Egyptian times, the prolific use of the element in Europe is attributed to the Gothic era. Profusely grouped upon several cathedrals, it heightens a sense of allegory and the fantastic.

Pinnacles

Unlike the flying buttress, the pinnacle started out as a structural element meant to deflect the pressures of the vaulted roof downward. They were imbued with lead, literally ‘pinning down’ the sideways pressures of the vault, served as counterweights to extended gargoyles and overhanging corbels, and stabilized flying buttresses. As their aesthetic possibilities began to be known, pinnacles were lightened and the flying buttress was structurally developed to handle the vaulted roof. Pinnacles are profusely used to break the abrupt change in slenderness, as the church building gives way to the mounted spire, lending the building a distinctively Gothic, tapering appearance.

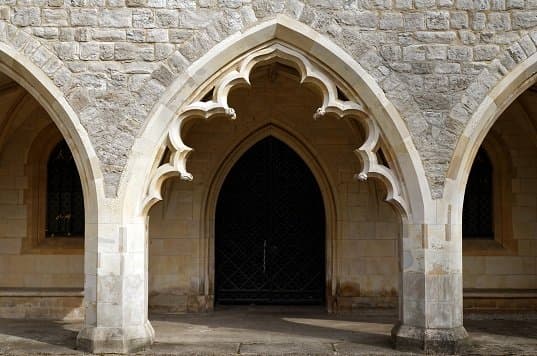

Pointed Arch

Recorded for the first time in Christian architecture during the Gothic era, the pointed arch was used to direct the weight of the vaulted roof downward along its ribs. Unlike the earlier Romanesque churches which depended solely on the walls to carry the immense weight of the roof, the pointed arches helped restrict and selectively transfer the load onto columns and other load-bearing supports, thereby freeing up the walls. It no longer mattered what the walls were made of, since (between the flying buttress and the pointed arch) they were no longer carrying any loads - thus the walls of Gothic cathedrals began to be replaced by large stained-glass windows and tracery.

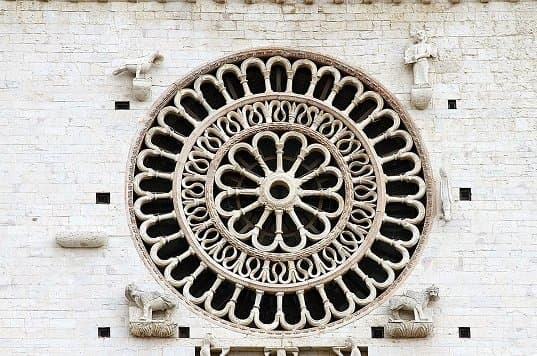

Tracery

Tracery refers to a series of thin stone frames, inlaid in window openings to support the glass. Bar tracery found expression in the Gothic period, with its lancet-and-oculus pattern that aimed at conveying a slenderness of design, and increasing the amount of glass paneling. Unlike in plate tracery, thin stone mullions were used to divide the window opening into two or more lancets. Y tracery was a specific variety of bar tracery that separated the window head using thin bars of stone, splitting in the shape of a Y. These delicate web-like tracings helped increase the glass-to-stone ratio and grew into florid detail as Gothic architecture developed further.

The Oculus

Two specific window designs were established during the Gothic period - the narrowly pointed lancet reinforced height, while the circular oculus held stained glass. As height grew less of an objective with Gothic builders, the latter half of the Rayonnant Gothic saw structures reduced to an almost-skeletal, diaphanous frame. Windows were expanded and walls replaced by traceried glass. An immense oculus on the triforium wall of churches formed a rose window, the largest of which is found at St. Denis. Divided by stone mullions and bars, it held radiating stone spokes like a wheel and was placed below a pointed arch.

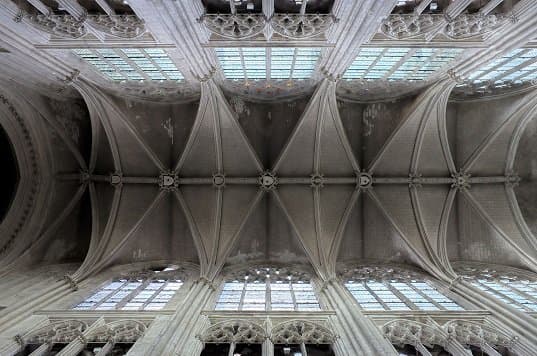

Ribbed Vault

Gothic architecture replaced Romanesque groin vaults with ribbed vaults to counteract the complexities of construction and limitations that allowed it to only span square rooms. Also known as ogival vaulting, ribbed vaulting developed with the need to transfer roof-loads better, while freeing up inner walls for tracery and glass. More ribs were added to the basic Romanesque barrel vault to increase the transfer of loads to the ground. As the Gothic era achieved its zenith, complex vaulting systems such as the quadripartite and sexpartite vaulting techniques were developed. The development of ribbed vaulting reduced the need for inner load-bearing walls, thereby opening up the inner space and providing visual and aesthetic unity.

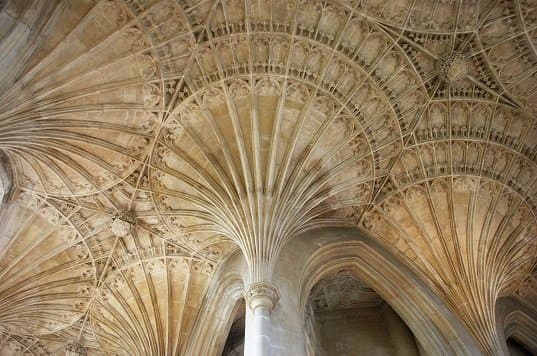

Fan Vault

One of the most obvious distinctions between the English and French Gothic styles, fan vaulting was used exclusively in English cathedrals. The ribs of the fan vault are curved equally and equidistantly spaced, giving it the appearance of an open fan. The fan vault was also applied during the reconstruction of Norman churches in England, doing away with the need for flying buttresses. Fan vaulting was used profusely in ecclesiastical buildings and chantry chapels.

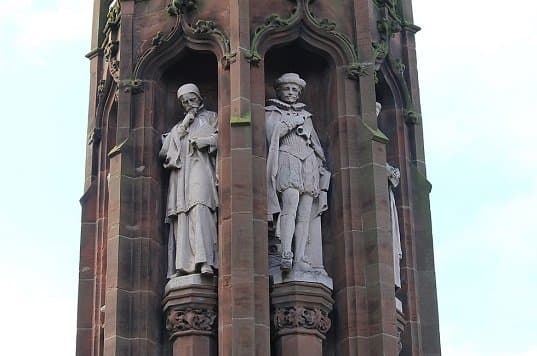

Statue Column

The Early Gothic era showcases some of the most detailed sculptures of the period. It was not uncommon to find statues that were of ‘structural’ nature, carved from the same stone as the column that held up the roof. Often depicting patriarchs, prophets, and kings, they were placed in the porches of later Gothic churches to lend an element of verticality. These larger-than-life depictions may also be spotted in the embrasures on either side of cathedral entrances. In France, column statues often depicted rows of finely-dressed courtiers, reflecting the prosperity of the kingdom.

List of Top 10 Most Spectacular Gothic Buildings

A list of the most impressive Gothic buildings, what makes them so special in architectural and artistic viewpoint, and their main attractions for travelers and pilgrims.