10 Greatest World War I Generals

Živojin Mišić (1855-1921)

Serbian Vojvoda Živojin Mišić was one of the most important figures on the Serbian Front at the outbreak of the war and later liberation of Serbia. In the Battle of Kolubara in late 1914, Mišić decisively defeated the overwhelmingly numerically superior Austro-Hungarian forces under the command of Oskar Potiorek. The Austro-Hungarian army was humiliated, while Serbia capitulated only after a coordinated attack of Austro-Hungarian, German and Bulgarian forces in 1915. Mišić withdrew with the Serbian Army through Montenegro and Albania to Greece. After the establishment of the Thessaloniki Front in 1916, he was appointed commander of the First Army and in mid-1918, Chief of Supreme Command. He commanded the Serbian army until the end of the war.

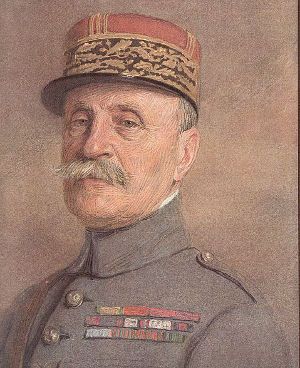

Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929)

Marshal of France Ferdinand Foch played a crucial role in checking the Germans at the beginning of World War I. In September 1914, he was the key actor in German defeat at the First Battle of Marne by which he effectively ended all German hopes to achieve a quick victory on the Western Front. After the failed offensive at Ypres in 1915 and huge casualties in the Battle of the Somme one year later, Foch was dismissed. But he was back as Chief of the French General Staff in 1917. In 1918, Foch was appointed Commander in Chief of the Allied Armies. After repulsing the German Spring Offensive, Foch co-created the so-called Hundred Days Offensive, which forced the Germans to give in.

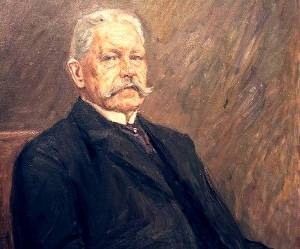

Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934)

When Paul von Hindenburg was re-called to military service and named commander of the German Eight Army in August 1914, he was in a seemingly lost position. He was facing the advancing Russian First and Second armies with overwhelming numerical superiority. But after defeating the Second Army in the Battle of Tannenberg and then the First Army in the Battle of the Masurian Lakes, he pushed the Russians out of East Prussia. According to many historians, von Hindenburg’s defeat of the Russian First and Second armies was a serious blow to the Russian morale and one of the key factors that led to the Russian Revolution of 1917. But on the other hand, the transfer of an entire German corps from the Western Front to confront the advancing Russians weakened the German positions in France. In addition, the Russians continued to pose a serious threat to the German ally Austria-Hungary.

Aleksei Brusilov (1853-1926)

Aleksei Brusilov was one of the most innovative World War I generals. In Galicia, the commander of the Russian Eighth Army laid down plans for a full-scale attack along the Austro-Hungarian lines. The so-called Brusilov Offensive began with some spectacular victories such as the Battle of Lutsk, which decimated the numerically superior Austro-Hungarian army. During the first two days of the offensive that started on June 4, 1916, the Austro-Hungarian forces suffered some 230,000 casualties, while the Russians advanced over 45 miles. By September 20, the Russian advance was finally halted thanks to the German troops that were transferred from the Western Front and the Russians running out of supplies. Although the Brusilov Offensive was the last major Russian campaign during World War I and despite the fact that the Russians suffered heavy casualties as well, the Russian general managed to break the Austro-Hungarian army. It didn’t launch any major offensive alone by the end of the war, while Brusilov’s success during the early phase of the campaign encouraged Romania to enter the war on the Entente’s side.

Douglas Haig (1861-1928)

British Field Marshal Douglas Haig was Commander in Chief of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from late 1915 when he replaced John French until the end of the war. He is remembered as the general who led the British forces in the Battle of the Somme in 1917 and the Battle of Passchendaele one year later, both of which achieved little despite heavy casualties. Although Haig’s contribution to the Allied victory over the Central Powers is undeniable, the British Field Marshal remains a subject of controversy. While some hold him responsible for the worst human losses in British history, others emphasize that he was above all a man of his time and that high casualties simply reflect the military reality of that time.

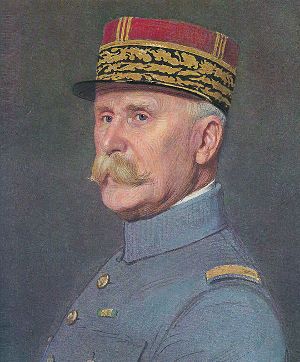

Philippe Petain (1856-1951)

Marshal of France Philippe Petain is best known as the leader of the so-called Vichy France and for collaboration with the Germans during World War II. But Petain was also one of the greatest World War I generals and was hailed as a national hero after repulsing the German attack at Verdun in 1916. One year later, he was briefly Commander in Chief but held the position long enough to improve discipline and raise morale, which was crucial for the French forces to withstand and repulse the massive German offensive in spring 1918. However, achievements during World War I didn’t help him escape trial for treason after the end of World War II. He was sentenced to death, but due to his age, the sentence was turned into life imprisonment.

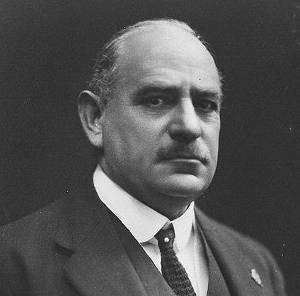

Armando Diaz (1861-1928)

Italian general and Marshal of Italy Armando Diaz is remembered for halting the Austro-Hungarian offensive in 1917 and launching a counter-offensive, which led to a decisive victory over Austria-Hungary. After the Italian entry into the war, he was major-general under Luigi Cadorna but was soon promoted to division and then corps commander. After the disaster at the Battle of Caporetto in fall 1917, Diaz replaced Cadorna as Chief of Staff of the Italian Army. He managed to stop the Austro-Hungarian advance along the Piave River and, in June 1918, led the Italian forces to a major victory in the Battle of the Piave River. A few months later, he achieved a decisive victory in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, which de facto ended World War I on the Italian Front.

John Monash (1865-1931)

Australian general John Monash was one of the architects of the Battle of Amiens, which opened the final phase of World War I. Monash led the 4th Brigade during the Gallipoli campaign in 1915-16. Despite the failure to secure an open sea route to Russia in the Mediterranean, he was appointed commander of the newly formed Australian 3rd Division in France. Following the success at the Battle of Messines in 1917, he was promoted to lieutenant general. Shortly after that, Monash replaced general William Birdwood as commander of the Australian Corps and led his corps to a series of victories in the final phase of the war. Contrary to the majority of both his Allied and Central Powers' counterparts, the Australian general was very productive in developing strategies to minimize casualties.

Svetozar Boroević (1856-1920)

Svetozar Boroević (born into a Serbian Orthodox family in Austria-Hungary) was one of the most capable Austro-Hungarian generals. After the outbreak of the war, he was sent to the Eastern Front, but following the Italian entry into the war, he was sent on the Austro-Hungarian-Italian border. Much better defensive than offensive strategist, Boroević achieved a major victory in the Battle of Caporetto in 1917, which allowed the combined Austro-Hungarian and German forces to advance over 60 miles. But the attempt to strike the Italian forces the final blow failed, and after the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, the Austro-Hungarian army collapsed. After the end of the war, Boroević offered his services to Belgrade, but he was rejected.

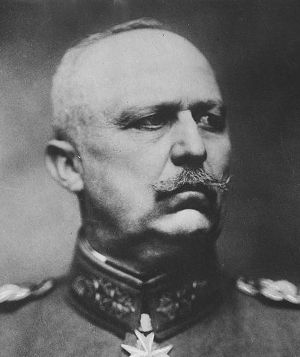

Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937)

German general Erich Ludendorff was one of the key actors in the victory over the Russians at Tannenberg, which, according to many historians, played an important role in the Russian Revolution and the subsequent Russian withdrawal from the war in March 1917. On the Western Front, however, Ludendorff was less successful. The German defeat in the First Battle of Marne revealed that his revised Schlieffen Plan, which foresaw a quick victory in the West had failed. In 1917, he also ordered unrestricted submarine warfare against Britain, intending to break the blockade. But while the attempt to break the blockade failed, his unrestricted submarine warfare helped provoke the US entry into the war. In March 1918, Ludendorff launched a full-scale offensive (known as the Spring Offensive) in the West, but despite some initial success, the German troops soon found themselves in the defensive. After the Second Battle of the Marne, Ludendorff realized that the war was lost, although he demanded the war to continue after he heard for the armistice conditions. He was rejected, and on October 26, he resigned.