Top 5 Mythical Sea Monsters That Terrorized Sailors

For centuries, sailers peered into the waves with fear and fascination, spinning tales of creatures lurking just beneath the surface. From colossal tentacled beasts dragging ships to their doom to seductive sirens whose song lured sailors to watery graves, these legends sprang from sailors nightmares, some born of misidentified sea life, others pure invention. Here are the five most famous sea monsters.

Kraken (Norse Legend, c. 1225)

Image: An 1887 engraving by Edgar Etherington depicting a giant octopus attacking a ship, from Monsters of the Sea. This dramatic artwork reflects 19th-century interpretations of the Kraken myth.The Kraken is a legendary sea monster from Norse mythology, often described as a massive, squid-like creature lurking in the deep oceans. Its origins trace back to ancient Scandinavian stories, including the 13th-century Norse sagas such as the "Heimskringla" by Snorri Sturluson. These early accounts told of a terrifying beast so large that sailors sometimes mistook its body for an island. When disturbed, it would unleash chaos, dragging entire ships and crews beneath the waves with its powerful tentacles.

Sailors of the North Atlantic, especially around Norway and Greenland, passed down chilling tales of the Kraken through generations. They spoke of monstrous arms reaching up from the depths, wrapping around the hulls of ships during storms, and pulling them into a watery grave. Some versions claimed the beast could create massive whirlpools just by diving beneath the surface, sinking anything in its path. At the time, these legends offered a way to explain the many mysterious shipwrecks and disappearances in the dangerous northern seas.

Although inspired by real sightings of giant squids, which can grow up to 40 feet long, the creature of myth is far larger and more destructive. Unlike its real-life counterpart, the Kraken of folklore is nearly unstoppable, a godlike force of nature that lurks beneath the waves, waiting for its next victim. Over the centuries, the Kraken has slipped from pure myth into popular culture, inspiring writers, artists, and filmmakers.

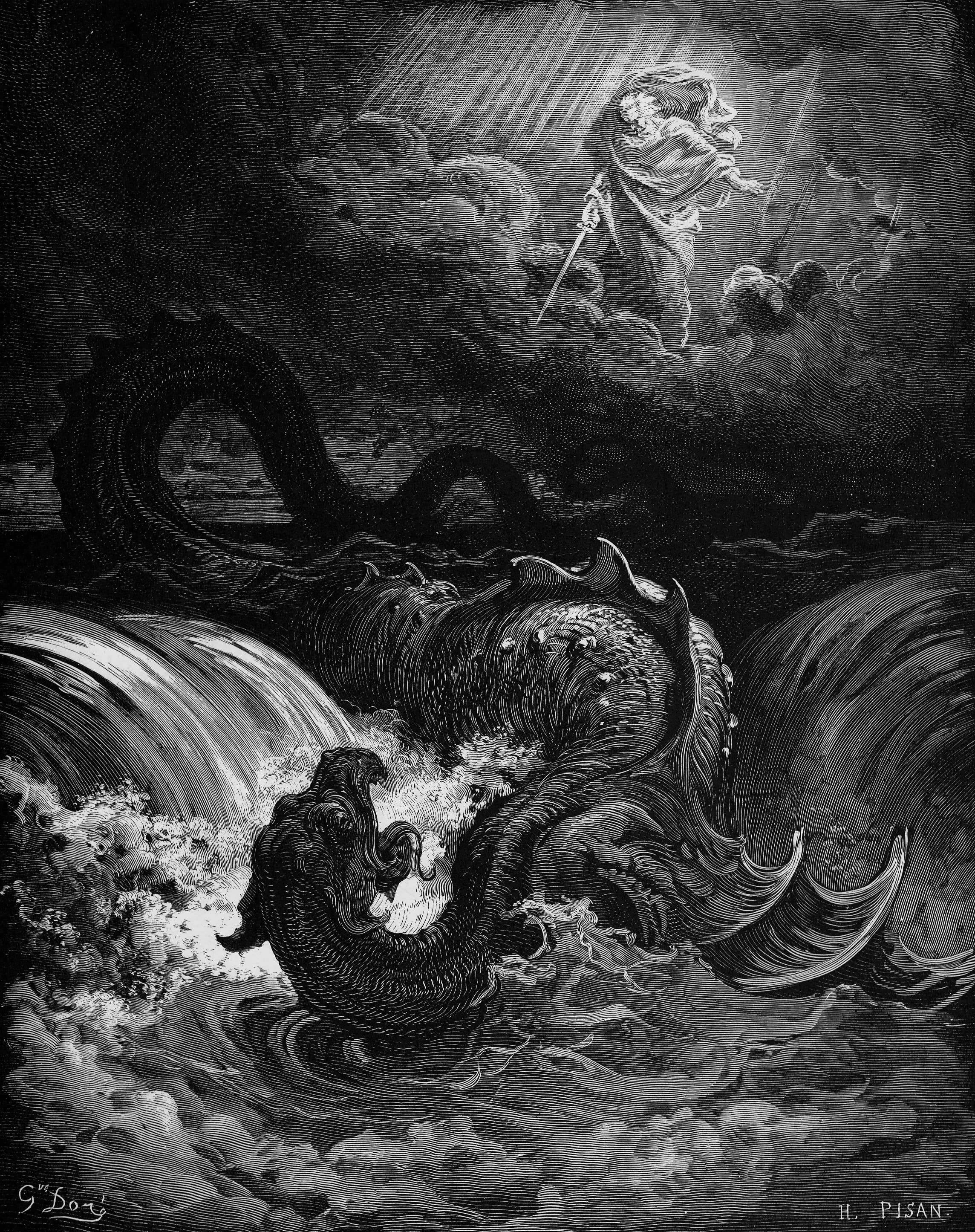

Leviathan (Hebrew Bible, c. 600 BCE)

Image: “The Destruction of Leviathan”, a dramatic 1865 engraving by Gustave Doré, depicting God slaying the Leviathan described in the Book of Isaiah.The Leviathan is one of the most powerful and mysterious creatures in ancient mythology. First mentioned in the Hebrew Bible around 600 BCE, it is described as a massive, twisting sea serpent that dwells in the deep oceans. Far more than just a large sea creature, the Leviathan symbolized untamed nature and overwhelming chaos. In one dramatic passage, God defeats the Leviathan to show His power over even the most fearsome forces in creation.

In biblical texts, the Leviathan is often described with terrifying features: eyes that shine like the morning sun, smoke pouring from its nostrils, and breath so hot it can ignite flames. It was said to churn the sea into a boiling cauldron with its movements and to be impossible for humans to defeat or tame. This portrayal captured the imagination of ancient peoples, who feared the deep sea and the unknown creatures that might lurk there.

During the Middle Ages, the legend of the Leviathan evolved. It began to appear in bestiaries, medieval books of animals both real and mythical, where it was seen as a symbol of evil, chaos, and even the devil himself. Artists of the time often depicted the Leviathan as a giant fish or dragon-like creature, its mouth wide open as if to swallow entire ships or even the souls of the damned.

The Leviathan continues to influence modern culture, often appearing in literature, films, video games, and art as the ultimate sea monster. Its name has even become a metaphor for something vast and uncontrollable, like a "Leviathan" storm.

Sirens (Greek Mythology, c. 8th century BCE)

Image: Ulysses and the Sirens (1891) by John William Waterhouse. This dramatic oil painting shows Odysseus tied to the mast of his ship, straining against his bonds with the Sirens, depicted here with birdlike forms.The Sirens are mysterious and dangerous creatures from ancient Greek mythology, first appearing in Homer's epic poem The Odyssey, written around the 8th century BCE. These beings were often described as having the bodies of birds and the faces of women, though later stories portrayed them more like mermaids. They lived on rocky islands in the sea and were known for their hauntingly beautiful singing voices, which could hypnotize any sailor who heard them.

According to the myth, the Sirens would sing irresistible songs that filled sailors with longing and made them forget everything else, even their own safety. Their music was so enchanting that ships would steer off course and crash into the jagged rocks surrounding their island, leaving the crew doomed to die. The Sirens didn't need to attack; they simply let desire and distraction do the work.

The Greek hero Odysseus famously outsmarted the Sirens during his long journey home. He ordered his crew to plug their ears with beeswax so they couldn't hear the song. Curious to hear it himself without falling under its spell, he had his men tie him tightly to the mast of the ship. As they sailed past the island, Odysseus was tormented by the Sirens' voices but couldn't steer the ship off course, and the crew rowed safely beyond danger.

Over the centuries, Sirens have continued to captivate the imagination, appearing in medieval literature such as Dante's Inferno, as well as in classical music, fine art, and even modern films.

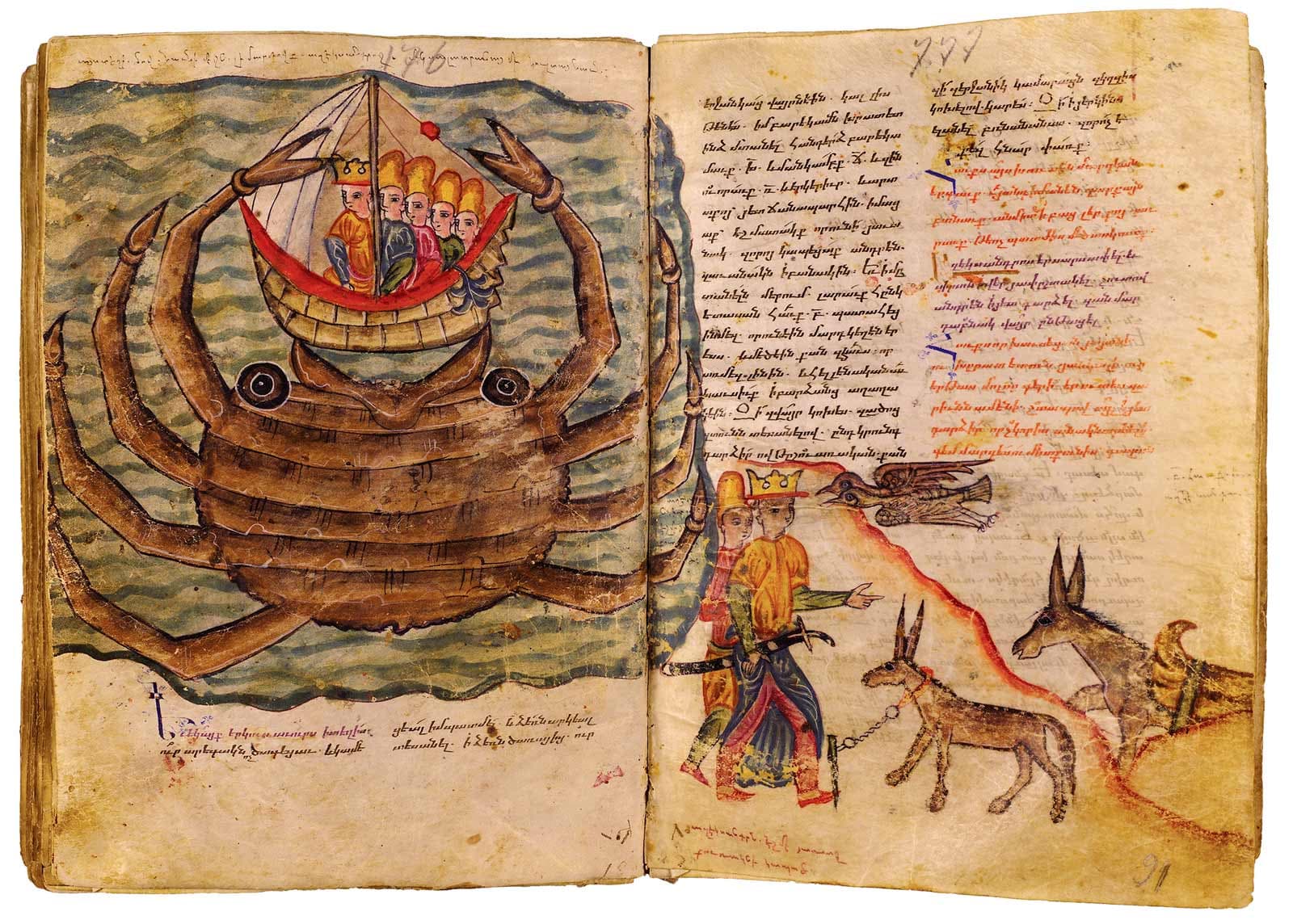

Aspidochelone (Physiologus, c. 2nd century CE)

Image: A 16th-century Armenian manuscript from the Alexander Romance, depicting a legendary encounter with the island-like Aspidochelone.The Aspidochelone is a mythical sea monster first described in the 2nd-century Christian text Physiologus as a colossal turtle or whale so vast that its rounded shell looked exactly like an island to passing sailors. Its very name comes from the Greek words *aspis* (“shield” or “asp”) and *chelōnē* (“turtle”), a fitting description for this “shield-turtle” of legend.

According to the old tales, unsuspecting mariners would row ashore, anchor their ships beside this “island,” and build fires to cook their meals. The creature, feeling its back burn, would suddenly dive deep into the ocean, dragging ship and crew down to a watery grave. As if that weren't enough, some accounts say the Aspidochelone emitted a strangely sweet scent that lured schools of fish within reach of its gaping jaws.

In medieval bestiaries the Aspidochelone became a moral lesson, symbolizing Satan's deceptions: just as the monster's fake island doomed sailors, so the Devil's temptations lead souls to ruin. Variations of the tale appear worldwide, the Irish Saint Brendan myth names the creature Jasconius, Norse sagas call it the Hafgufa, and even Inuit lore tells of the Imap Umassoursa, another “island” beast that submerges under curious visitors.

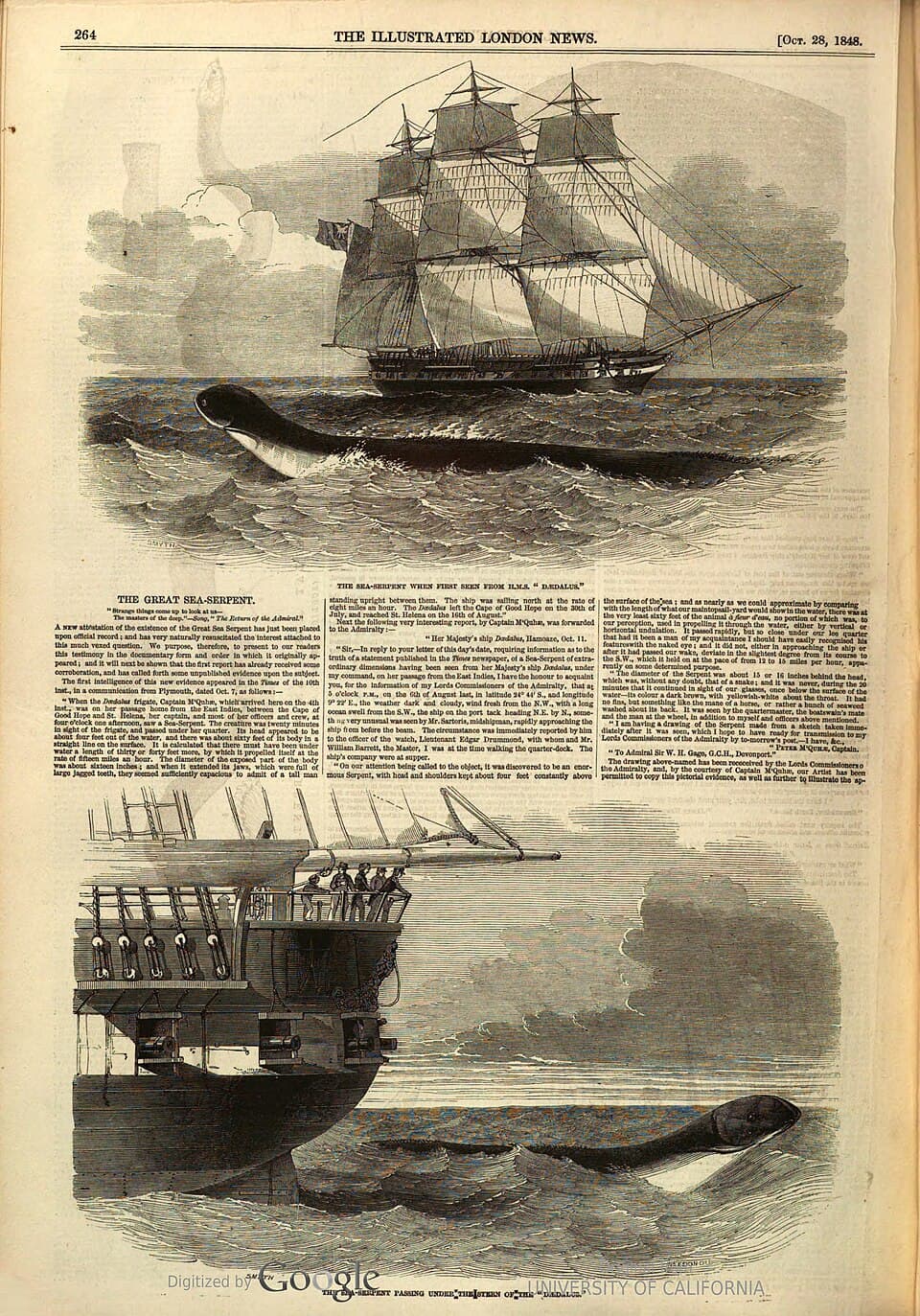

Sea Serpent (Early Modern Sightings, c. 1700s)

Image: An 1887 engraving by Edwin Weedon, based on an 1848 eyewitness account by the crew of HMS Daedalus, who reported seeing a massive sea serpent in the South Atlantic Ocean.Stories of long, serpentine creatures gliding through the waves began to surface in sailors' logs as early as the 1700s, with reports coming from both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Witnesses described seeing line after line of undulating humps breaking the water's surface, sometimes stretching for scores of feet, giving the impression of a colossal sea snake slithering beneath their ships.

One of the most famous 19th-century encounters occurred on August 6, 1848, when the crew of the Royal Navy's HMS Daedalus reported an enormous serpent in the South Atlantic, about 300 miles off Namibia. The ship's officers noted a creature at least sixty feet long, with four feet of its head rising above the surface, and watched it swim by for twenty minutes before it vanished into the depths.

A year after the Daedalus sighting, sailors aboard HMS Plumper off Portugal thought they saw the same beast, only for later analysis to suggest it may have been a sei whale's jaw breaking the surface. Today, many scientists believe such sightings can be attributed to large whales, like sei or Bryde's whales, surfacing in a way that mimics a long, sinuous back.