10 Most Distinguished Works of Ancient Egyptian Art

Narmer's Palette (31st Century BC)

A small dark green schist stone which is carved into a shield-shaped ceremonial palette depicts pharaoh Narmer’s rise to power. But since Narmer is by many Egyptologists identified as (Pharaoh) Menes, the first ruler of the unified Egypt and the founder of the First Dynasty, the Narmer’s Palette thus also represents the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. The 23 inch high palette is decorated on both sides and has the distinction of being one of the oldest known ‘canvases’ of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing as well as being the oldest historical document in the world. It is now housed in the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada.

Khufu's Statue (26th Century BC)

The small ivory statue of Pharaoh Khufu (Cheops) is the only Khufu’s portrait discovered so far. Next to the Great Pyramid, the 7.5 cm (3 inch) statue is the only physical evidence of Khufu’s two decade-long reign. It was found by the famed English Egyptologist Flinders Petrie at the ancient necropolis of Abydos, south of the Temple of Osiris. Petrie’s team, however, had a problem. They uncovered the statue without its head. Luckily, they managed to find the missing head and the builder of the Great Pyramid finally got a face. Khufu’s Statue is today housed in the Cairo museum.

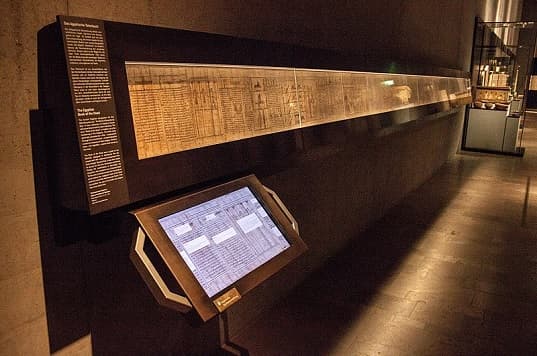

Egyptian Book of the Dead (16th Century BC)

Known to ancient Egyptians as the ‘Book of Coming Forth by Day’, the scroll was entombed with various people who were wealthy enough to afford such vital guide through the Underworld. One of these scrolls, belonging to a woman named Anhai who died in about 1100 BC (currently housed in the British Museum) is more than seventeen feet long when unrolled. The writings are a compilation of magic spells that assisted the deceased on their journey through the western land, amid a torrent of gods, monsters, and giant snakes. The spells were instructional and were adorned with beautifully intuitive pictures to ward off danger and gain the strength of lurking gods. Intricate and foretelling, the presence of familiar gardens, houses, animals, boats, family members, clothes, and food lavished the spiritual sojourner with understanding, comfort, and wisdom.

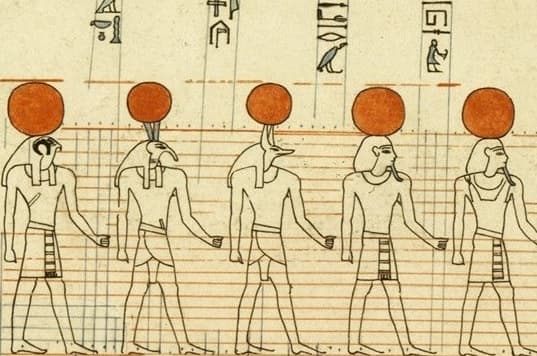

Astronomical Ceiling, Tomb of Senenmut (15th Century BC)

Senenmut was the architect of the renowned Pharaoh Hatshepsut’s tomb complex although his own tomb is just as stunning. It features an astronomical map on the ceiling which is the world’s oldest map of its kind. The map consists of two sections - northern hemisphere and southern hemisphere. The northern section includes the earliest known twelve month Egyptian calendar illustration and representations of the northern constellations. The southern section of the map, on the other hand, lists decans (stars) and planets visible to the naked eye. Surprisingly, however, Mars is absent.

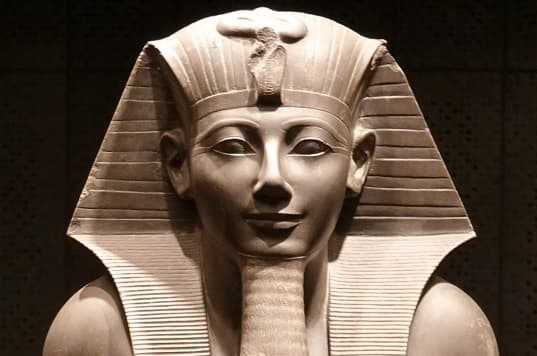

Thutmose III Statue (15th Century BC)

A basalt statue of Thutmose III is an artistic masterpiece, immortalizing the sixth Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. The stance of the statue and the gaze create an effect of a graceful yet powerful king. The face, however, also reflects a glimmer resemblance to his stepmother, aunt and temporary co-regent, Hatshepsut, all of whose statues he had destroyed when becoming a sole ruler. The statue that reveals the Pharaoh’s identity in the carved cartouche on his belt is housed in the Luxor Museum.

Amarna Period Art (14th Century BC)

During this period that coincides with the rule of pharaoh Akhenaten, ancient Egyptian art takes a distinctly unique form. People are depicted more realistically and life-like, their movement fluid, showing them in more intimate situations. Art wasn’t idealistically stiff and rigid anymore although the Pharaoh was always depicted lovingly with his family. Akhenaten himself is depicted with a large head, a long chin, and a less than perfect body; seeming to reveal who he was in reality rather than a physically perfect king. After Akhenaten’s death, however, ancient Egyptian artists returned to the previous artistic style.

Nefertiti Bust (14th Century BC)

A limestone bust, layered with painted stucco, immortalizes Akhenaten’s wife Nefertiti. The bust was created artist Thutmose and according to some, it represents the apex of the Amarna Period art. Nefertiti’s name meant ‘the beautiful one has come’ and admiration for her beauty is bestowed upon the statue by its artist. Although little is known about Nefertiti, the bust made her one of the most iconic figures of the ancient Egypt and antiquity as a whole. Since 1924, the Nefertiti Bust is in Berlin but the Egyptian authorities have been demanding its return ever since.

Tutankhamun's Golden Death Mask (14th Century BC)

Akhenaten’s son and successor Tutankhamun died at the age of 19 years, most likely from an infection which he developed after breaking his leg. He was buried with a twenty-four pound golden death mask that was placed over his head and shoulders. The mask is made from solid gold and is inlaid with blue glass, lapis lazuli and various semiprecious stones. It is thought to be slightly idealized but there is a general agreement that it is essentially a realistic portrait of the ‘Boy King’. Tutankhamun’s mask is housed in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum.

Throne of Tutankhamun (14th Century BC)

Tutankhamun’s cuboid-shaped throne was one of the most spectacular things Howard Carter saw when he entered the Pharaoh’s intact tomb in 1922. It is made from solid wood and covered with sheet gold and silver, and inlaid with semiprecious stones, colored glass and faience (ceramic). The overall style of the throne is one of the finest examples of the Amarna Period art which is reflected in the sun disc on the backrest (symbolizing Amun), more naturally styled birds and plants, scenes of the affectionate royal couple, and the physical features of the Pharaoh and his queen who are depicted with a high degree of realism.

Statue of Cleopatra VII Philopator (1st Century BC)

The black basalt statue is one of the most pristine images of the last Egyptian pharaoh, Cleopatra VII, presenting her in the midst of a stride, wearing a long form-fitting dress. The statue reveals the influence of ancient Greek art; Cleopatra wears a corkscrew wig and holds a cornucopia, a horn of plenty - though the front of her headdress is adorned with a uraeus (royal snakes), symbolic of Egyptian royalty. In her other hand she holds the ankh, the ancient hieroglyph meaning life. This masterpiece is housed at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

10 Must-See Masterpieces of Ancient Greek Art

Explore 10 Iconic Masterpieces of Ancient Greek Art.

Explore Now